The Civil War saw the introduction of the Medal of Honor, an award that would come to represent the highest military honor in the United States. By the end of the war, 328 U.S. Navy Medals of Honor had been awarded. Of those, eight were awarded to U.S. Navy people of color. Seaman Joachim Pease, one of these recipients, is often overshadowed by larger figures of the American Civil War. Though recognized as one of the first people of color awarded the Medal of Honor, little is known about Pease beyond the information listed in his award citation.

His official citation reads: PEASE, JOACHIM, Seaman, USN. Born Long Island, N.Y. Accredited to New York. (G.O. 45, 31 December 1864)

Served as seaman on board the U.S.S. Kearsarge when she destroyed the Alabama off Cherbourg, France, 19 June 1864. Acting as loader on the No. 2 gun during this bitter engagement, PEASE exhibited marked coolness and good conduct and was highly recommended by his divisional officer for gallantry under fire.1

On display at the National Museum of the United States Navy, his medal is easily overlooked in its oversized case amongst other Civil War artifacts. The medal is a simple five-pointed star tipped with trefoils with the relief engraving of Minerva repulsing Discord on the obverse and an engraving on the reverse "Personal Valor / Joachim Pease / (Colored Seaman) / U.S.S. Kearsarge / Destruction of the Alabama / June 9, 1864."

While information about Joachim Pease is scarce, the published record misrepresents what we now know about him. His enlistment record, early time serving on a whaling ship, and analysis of the Official Reports from the USS Kearsarge during its infamous battle with the CSS Alabama sheds new light on his journey to America, career as a Sailor in the United States Navy, and furthers the story of people of color in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War.

Enlistment Record

Joachim Pease appears on the U.S. Naval Enlistment Rendezvous records for New Bedford, MA for the week ending January 18, 1862. Pease enlisted on January 13 for three years at the rank of Ordinary Seaman. He is described in the record as 20 years of age, with black eyes, black hair, Negro complexion, and standing five feet six-and-a-half inches tall.2

The National Archives and Records Administration transcription of the Enlistment Rendezvous lists his birthplace as "Togo Island". An analysis of the rest of the information on this page of the Enlistment Rendezvous record indicates that this information is incorrect. According to the header on the record, the place of birth is recorded as "City, town, or country." For most enlistees on this record, the place of birth is written in the format City, State. Those from foreign countries have only the country name listed, with Ireland and St. Helena as examples from this record. The format of Pease's entry lends credence to the idea that he is from a foreign country, as opposed to the Long Island, New York accreditation in his citation.

Additional analysis of the handwriting on the rest of this page indicates that the T in Togo Island is actually an F, thus changing his birthplace to Fogo Island. The structure of the F matches the letter "F" on other line numbers on the same document, with all lines on the page appearing penned by the same hand. There are two Fogo Islands in the world. One located in Newfoundland, Canada, and the other in Cape Verde, Africa. While some online sources cite Fogo Island, Newfoundland as his place of birth, Newfoundland has an extensive genealogical index and no records matching similar names for Joachim Pease have been found.

The second Fogo Island is part of a group of islands that make up the country of Cape Verde located off the coast of West Africa. The Cape Verdean Maritime Exhibit at the New Bedford Whaling Museum indicates that Cape Verde was a common stop for whaling ships that were looking to resupply during their voyages. It was not uncommon for islanders of Cape Verde to join the crews of the passing vessels.3 It is probable that this is how Joachim Pease first came to the United States. There is a listing for a "Joakim Pease" in the ship log of the whaling ship Kensington out of New Bedford, MA while on her 1857-1861 voyage.4 Since his Navy enlistment record states he was 20 at his enlistment, it would mean Pease was born in 1842. Upon the embarkation of the Kensington, Pease would have been 15 years old. At the completion of the ship's voyage, he would have been 19 years old; making his time on the Kensington his likely journey to America. The Kensington closed out its logbook in November 1859.5 Following his arrival to the United States on the Kensington, the trail fades until Pease enlists with the Navy.

At the time of his enlistment, Pease is rated at the rank of Ordinary Seaman. The qualifications for an Ordinary Seaman during the Civil War require a Sailor to have served with the Navy for at least two years or have experience serving at sea. In addition to their normal duties, Ordinary Seamen oversaw the Landsmen, those over the age of 18 without prior service at sea.6 This indicates that Pease had prior sea service before enlisting with the Navy, further supporting the idea that he had previously served on the whaling vessel. The question of why he decided to join the Navy may be answered by pay.

The pay for a Sailor serving in the Union Navy was better than the pay serving on a whaling vessel. For a sailor on a ship like the Kensington, the crew would receive pay equivalent to 1/8 to as small as 1/350 of a share for a greenhorn. This percentage could result in pay as small as $25 for several years of work.7 This is in stark contrast to the salary in the Union Navy. Monthly pay for an Ordinary Seaman was $14 while an Able Seaman received pay at $18.8 With his enlistment as an Ordinary Seaman, he was assigned to the newly commissioned Union Navy ship USS Kearsarge.

The Voyage of the USS Kearsarge and battle with CSS Alabama

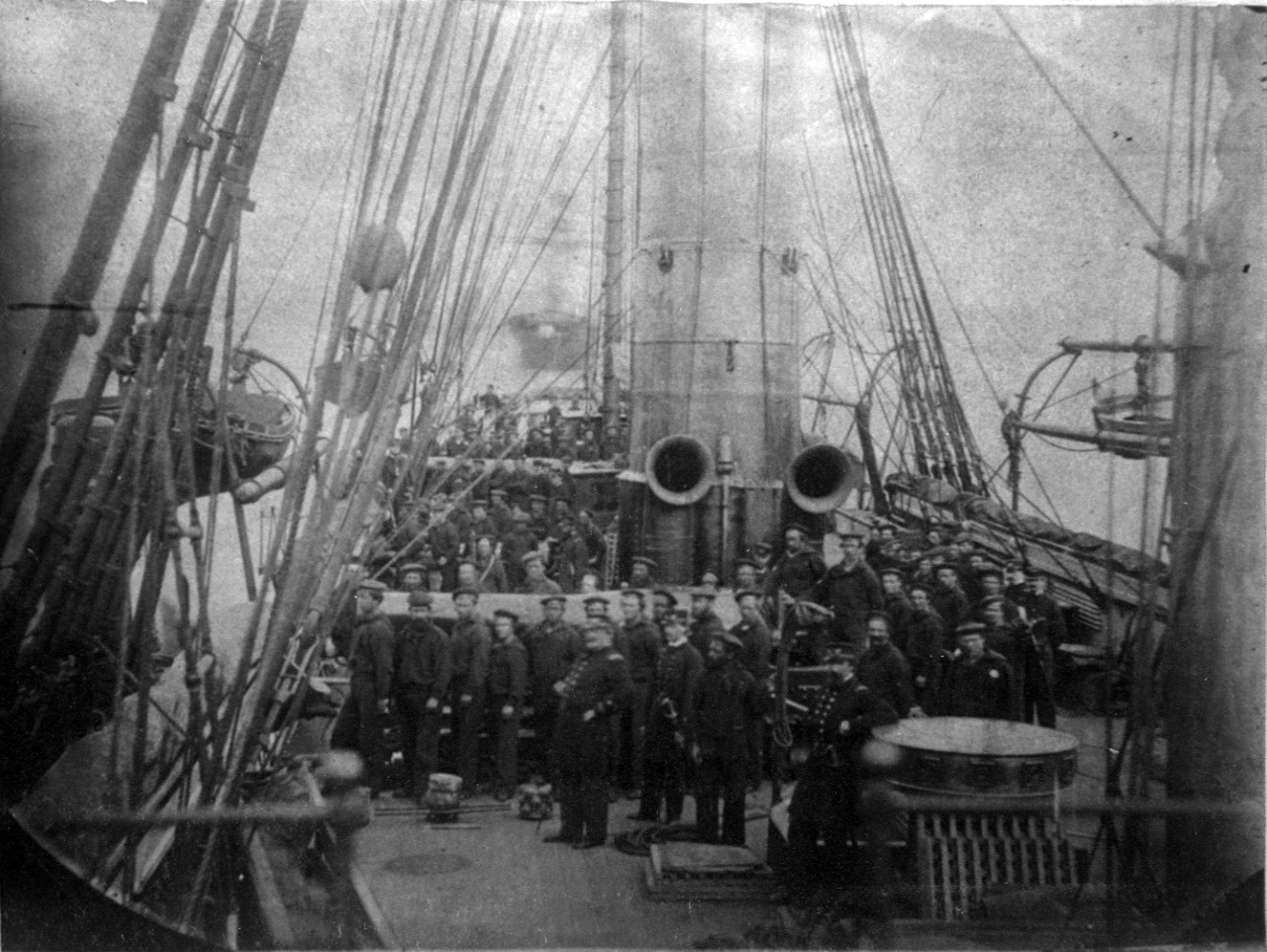

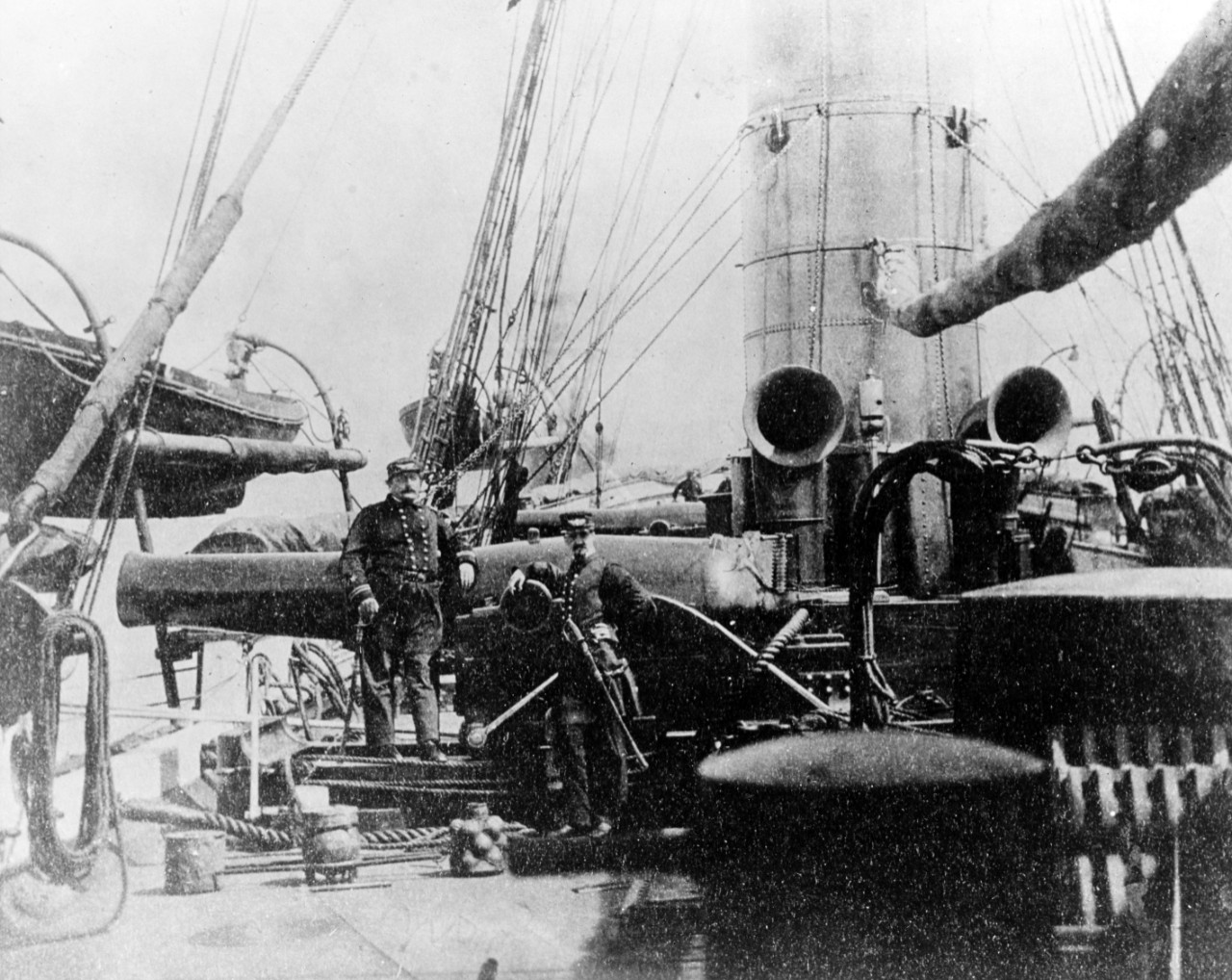

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Ship's crew at their battle stations, shortly after her June 1864 action with CSS Alabama. View looks aft from the forecastle, showing both XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbore cannon trained to starboard, as they were during the fight. Portly officer in the center foreground appears to be Acting Master James R. Wheeler.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Ship's crew at their battle stations, shortly after her June 1864 action with CSS Alabama. View looks aft from the forecastle, showing both XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbore cannon trained to starboard, as they were during the fight. Portly officer in the center foreground appears to be Acting Master James R. Wheeler.

The Kearsarge was a Mohican-class sloop of war commissioned on January 24, 1862. She was armed with a total of seven guns.9 Her battery consisted of two 11-inch smoothbore pivot guns, four 32-pounder smoothbores, and one 30-pounder rifled howitzer. The two pivot guns were located along the centerline of the main deck. This allowed for even distribution of weight while underway but also allowed the guns to be pivoted to the side needed for action. The 30-pounder was located on the forecastle on a mobile carriage that allowed it to be positioned as needed. The four 32-pounders were located on the gundeck, the deck below the main. They were arranged with two on port and two on starboard. The fully loaded USS Kearsarge departed Portsmouth, NH, on February 5, 1862 to hunt European waters for Confederate raiders who were wreaking havoc on American vessels bound for Union ports.

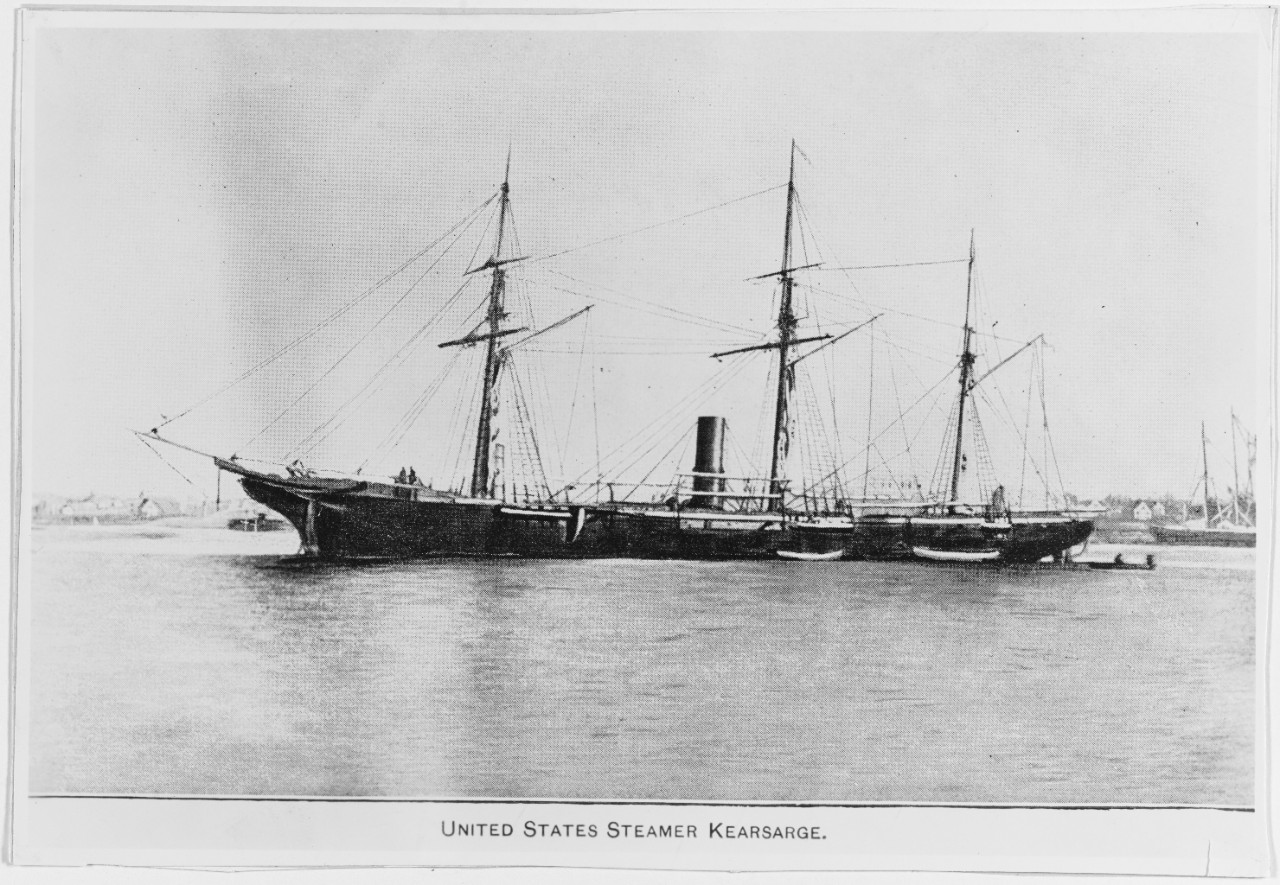

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Halftone reproduction of a photograph taken in late 1864, upon the ship's return to the United States from European waters.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Halftone reproduction of a photograph taken in late 1864, upon the ship's return to the United States from European waters.

From the time of her departure until June 1864, the Kearsarge had not actively engaged with Confederate ships. She assisted with the blockade of CSS Sumter in Cadiz, Spain, as well as CSS Rappahannock and CSS Florida, but without any direct engagements. By 1864, the main target for Union warships was the CSS Alabama. Since the Alabama's commissioning in August 1862, she was credited with the attack and sinking of one Union warship, USS Hatteras, and burning 55 American vessels.10

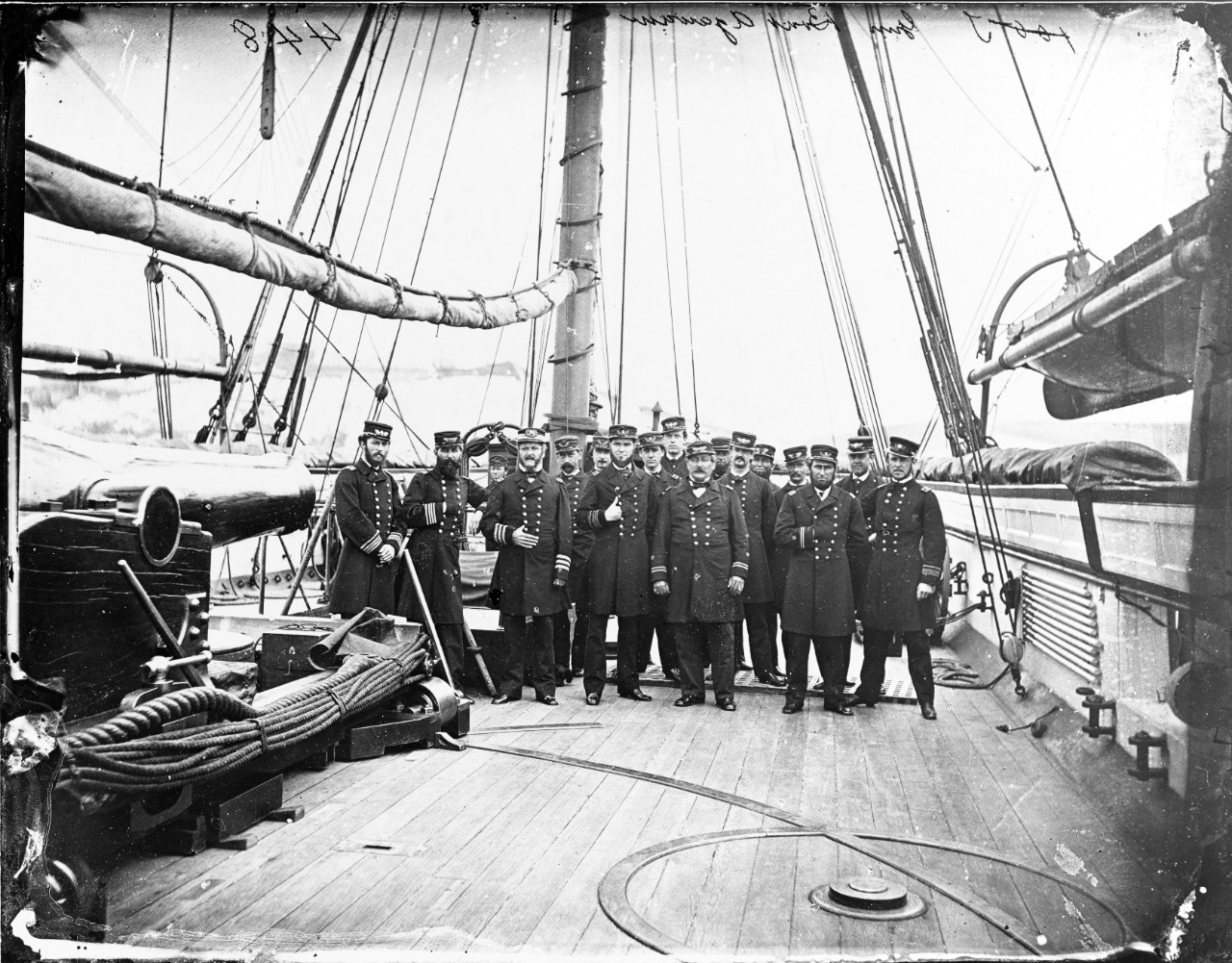

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Ship's officers pose on deck, at Cherbourg, France, soon after her 19 June 1864 victory over CSS Alabama. Her Commanding Officer, Captain John A. Winslow, is 3rd from left, wearing a uniform of the 1862 pattern. Other officers are generally dressed in uniforms of 1863-64 types. View looks aft on the port side. At left is Kearsarge's after XI-inch Dahlgren pivot gun, with its training tracks on the deck alongside.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) Ship's officers pose on deck, at Cherbourg, France, soon after her 19 June 1864 victory over CSS Alabama. Her Commanding Officer, Captain John A. Winslow, is 3rd from left, wearing a uniform of the 1862 pattern. Other officers are generally dressed in uniforms of 1863-64 types. View looks aft on the port side. At left is Kearsarge's after XI-inch Dahlgren pivot gun, with its training tracks on the deck alongside.

On June 12, 1864, Captain Winslow of USS Kearsarge received word that CSS Alabama had put in at Cherbourg, France. The Kearsarge immediately left her patrol near England for France, arriving off Cherbourg on 14 June11. That same day, Captain Semmes of CSS Alabama sent word to the U.S. Consul that he intended to fight the Kearsarge12. After making his intentions known, he requested coal for the Alabama13. Coaling took several days. Delayed by the coaling issue and poor weather, the Alabama was not able to engage the Kearsarge until June 19.

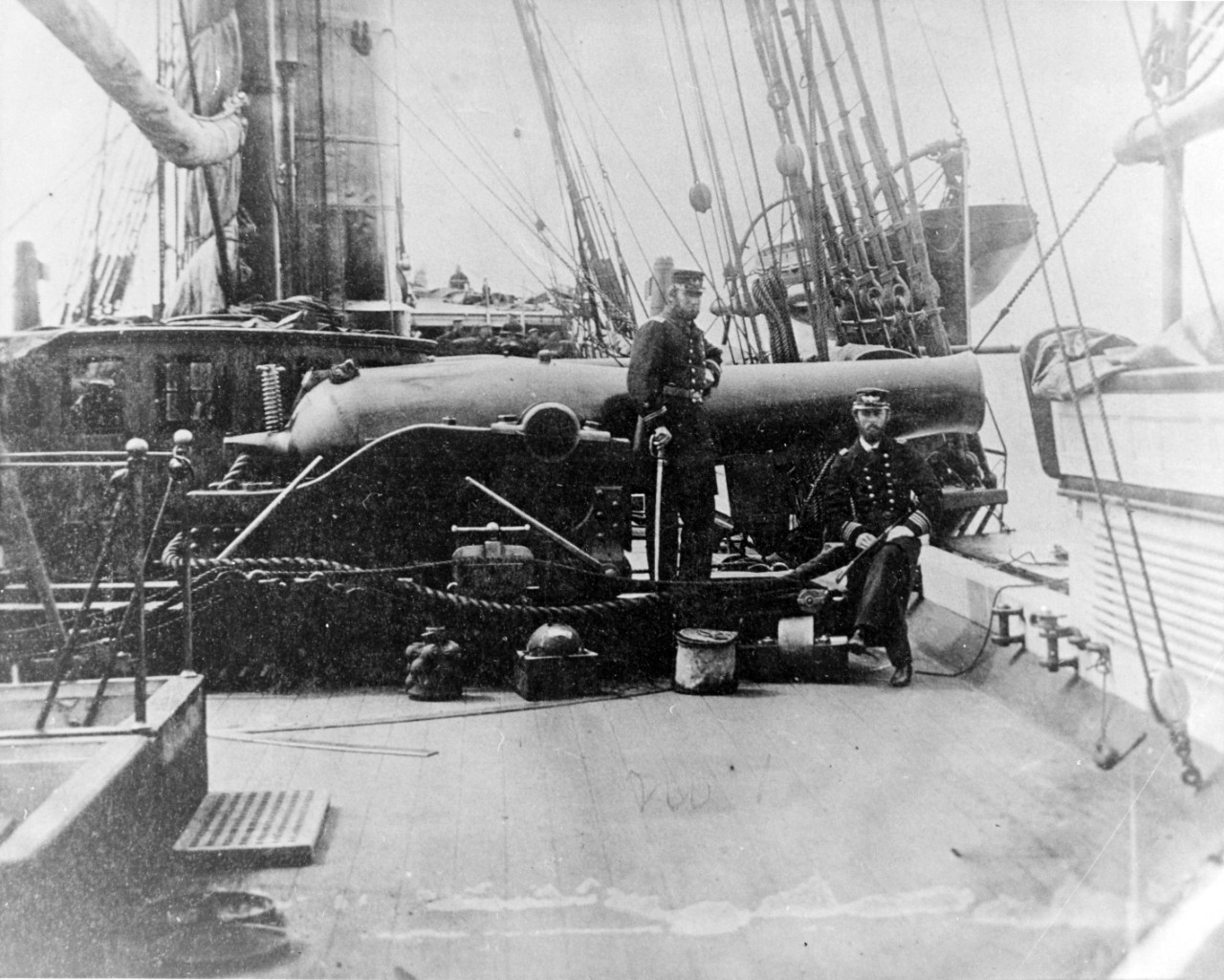

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) View on deck, looking forward along the starboard side in June 1864. Acting Master Eben M. Stoddard (left) and Chief Engineer William H. Cushman are beside the ship's after XI-inch pivot gun, which is trained out to starboard, as it was during the action with CSS Alabama on 19 June. Note ammunition for the gun on deck at left, including grape, shell and what appears to be a powder charge.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) View on deck, looking forward along the starboard side in June 1864. Acting Master Eben M. Stoddard (left) and Chief Engineer William H. Cushman are beside the ship's after XI-inch pivot gun, which is trained out to starboard, as it was during the action with CSS Alabama on 19 June. Note ammunition for the gun on deck at left, including grape, shell and what appears to be a powder charge.

Sunday morning, June 19, the CSS Alabama sailed out of Cherbourg under the escort of the French ironclad Couronne to engage with USS Kearsarge14. The French ship, only intending to enforce the neutrality of French waters, withdrew once the ships exceeded the three-mile limit. The Alabama's guns opened up at 10:57am. At approximately 11:00am, the Kearsarge returned fire15. Both ships engaged in a continuous starboard broadside as they circled each other seven times before the Alabama capitulated.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) View on deck, looking aft along the starboard side in June 1864. Acting Master James R. Wheeler (left) and Assistant Engineer Sidney L. Smith are standing beside the ship's forward XI-inch pivot gun, which is trained out to starboard, as it was during the action with CSS Alabama on 19 June. Note ammunition for the gun on deck at left, including canister (or a powder charge), shell and grape.

USS Kearsarge (1862-1894) View on deck, looking aft along the starboard side in June 1864. Acting Master James R. Wheeler (left) and Assistant Engineer Sidney L. Smith are standing beside the ship's forward XI-inch pivot gun, which is trained out to starboard, as it was during the action with CSS Alabama on 19 June. Note ammunition for the gun on deck at left, including canister (or a powder charge), shell and grape.

Of the Kearsarge's seven guns, five were engaged in the fight: the two 11-inch pivot guns, the two starboard 32-pounders, and the 30-pounder on the forecastle. The gunner's report seems to indicate that a 12-pound howitzer was also used, though Captain Winslow does not mention this in his reports. The 12-pounder might be the stern gun. Though accounts vary, the Kearsarge's Gunner reported that the engagement lasted for 65 minutes16.

According to Captain Winslow's report, the gunners were "cautioned against rapid firing without direct aim."17 The heavy guns, consisting of the two 11-inch pivots, were instructed to aim below the water line causing structural damage and flood the ship, while the lighter guns, the 30 and 32-pounders, were to clear the decks of sails, rigging, and personnel. Though the Alabama fired more projectiles, of those that hit the Kearsarge, none caused catastrophic damage. The Kearsarge's guns were more accurate and far deadlier.

As with all warships, the guns were organized into divisions. The first division was comprised of the forward 11-inch pivot gun and the 30-pounder on the forecastle, the latter manned by Marines. The second division was made up of the aft 11-inch pivot gun. The third division was comprised of the 32-pounders located on the gun deck.18 As shown by the number designation of the pivot guns, guns were "numbered from forward, beginning with No. 1, and continuing aft in succession."19 Looking at the 32-pounders, the number No. 1 gun was located on the forward portion of the gundeck while the No. 2 gun was located aft on the gundeck.

Acting Master David H. Sumner was the commander of the third division. After the battle, he submitted the following report to the Captain:

But among those showing still higher qualifications I am pleased to name Thomas Perry (boatswain's mate) and John Hayes (coxswain), first and second captains of No. 2 gun; George E. Read, first loader of same gun; also Robert Strahan (captain top), first captain of No. 1 gun; James H. Lee, sponger, and Joachim Pease (colored seaman), loader of same gun.20

Though the citation for Pease states that his medal was for "acting as loader on the No. 2 gun,"21 a close read of Sumner's report shows that Pease was the loader on the No. 1 gun, not the No. 2 gun. During the battle with the Alabama, Pease was most likely serving as a loader on the forward starboard 32-pounder, located on the gundeck.

At the end of the battle, the Alabama was riddled with holes and sinking fast. Kearsarge, though damaged, was still serviceable. She assisted in the recovery of the men from the Alabama and returned to Cherbourg. Following the battle with the Alabama, Kearsarge continued her cruise for Confederate raiders before returning to the United States, docking at Charlestown Navy Yard, Boston, on November 7, 186422. She decommissioned on November 26 for repairs with the crew being discharged on November 3023,24.

Following the arrival of the Kearsarge at Boston Harbor, Joachim Pease seemingly disappears from the written record. According to his enlistment record, his term of enlistment expired on January 13, 1865. Further research for evidence of a naval career or return to Cape Verde have yet to prove successful. Genealogical records searches in Cape Verde using Catholic Diocese records proved unsuccessful in locating Joachim or his descendants. While it is possible, he returned to Cape Verde, it is equally possible that he continued as a sailor living his life at sea. The Harbormaster log in Boston Harbor in 1865 listed a plethora of civilian ships that Joachim Pease could have served on following his time in the U.S. Navy, although the location of the logs of these civilian ships is unknown.

Conclusions

Joachim Pease is awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions on the Kearsarge in accordance with Navy General Order 45 on December 30, 1864, along with 146 other Army and Navy Medal of Honor recipients.25 Out of the 146 recipients awarded the medal on this General Order, Pease was one of the five people of color. Though awarded, Pease never received his medal. The most likely reason is simply that he could not be found after the war. His name does not appear again in the enlistment records or muster rolls of any U.S. Navy ship nor does his name appear in any census records. The Medal of Honor for Pease was transferred as part of a collection from the Bureau of Medals to the Naval History and Heritage Command in 1957 with other Medals of Honor, those not presented, and medals engraved for issue but revoked.

The journey of Joachim Pease enlightens us with possibilities of something rare in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, an African receiving the highest U.S. military award as a man of color. He is also unique in that he was able to hold higher rank than many other African-Americans. Both former slaves and free people of color serving onboard Union ships were usually only able to hold the rank of Boy or Landsman. He was a competent and valued Sailor as shown by his initial rank of Ordinary Seaman, his promotion to Seaman while aboard the Kearsarge, and the division commander's praise in the after action report to the Captain show his exemplary behavior as a Sailor. There is much hope that his story can prompt more inspiration in the research of these early pioneering people of color.

1 http://www.cmohs.org/recipient-detail/1043/pease-joachim.php

2 U.S. Naval Enlistment Rendezvous, 1855-1891 for Joachim Pease; https://search.ancestrylibrary.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?indiv=1&db=FS1USNavalEnlistmentRendezvous&h=104421

[3] Cape Verdean Maritime Exhibit, New Bedford Whaling Museum exhibit https://www.whalingmuseum.org/explore/exhibitions/current/cape-verdean-maritime

[4] New Bedford Whaling Museum, Whaling Crew List Database

[5] New Bedford Whaling Museum, Logbook Database https://www.whalingmuseum.org/introduction-whaling-logbooks-and-journals

[6] Steven John Ramold, "Valuable Men for Certain Kinds of Duty: African Americans in the Civil War Navy" (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Nebraska, 1999), 81.

[7] New Bedford Whaling Museum, Life Aboard https://www.whalingmuseum.org/learn/research-topics/overview-of-north-american-whaling/life-aboard

[8] Military Pay/Civil War History. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/military-pay

[9] Official Records, 80.

[10] Ibid., 681.

[11] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 3. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896), 50.

[12] Ibid., 648

[13] Ibid., 652

[14] Ibid., 79.

[15] Ibid., 64.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 79.

[18] Ibid., 66.

[19] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series 1, Vol. 3. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896), 14.

[20] Official Records, 67.

[21] The Navy. Medal of Honor 1861-1949.

[22] Ibid., 350.

[23] "Kearsarge I (Sloop-of-War)." Naval History and Heritage Command. July 28, 2009. Accessed April 26, 2018. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/k/kearsarge-i.html

[24] William Marvel, The Alabama & the Kearsarge: The Sailor's Civil War. (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 273.

[25] https://archive.org/stream/generalordersofwunit/generalordersofwunit_djvu.txt